Saturday, October 23, 2010

By David T. Rowlands, from Green Left Weekly

Peruvian President Alan Garcia, who last year ordered the brutal massacre of protesting Amazonian tribespeople, has once again resorted to violence — this time in person.

Visiting Edgardo Rebagliati Hospital in Lima, on October 9, Garcia encountered 27-year-old Ricardo Galvez, who shouted “corrupt” at the president. Eyewitnesses say Garcia flew into an uncontrollable rage and forcefully struck the volunteer worker in the face.

Members of Garcia’s entourage landed follow up blows, knocking a defenceless Galvez to the floor where he was subjected to further mistreatment.

A dazed and bleeding Galvez was dragged away and detained by security personnel. However, the spontaneous intervention of fellow hospital workers and patients expressing their solidarity with Galvez secured his release.

This is not the first time Garcia has publicly assaulted a citizen. In 2004, Garcia kicked a protestor out of the way, later denying the incident occurred until footage surfaced.

Garcia admits to verbally attacking Galvez but denies striking him. In fact, within hours of the incident, the Garcia camp had concocted a farcical story about a patriotic hospital cleaner who had spontaneously punched Galvez to defend the honour of the nation’s head of state.

The “cleaner” in question came forward and made a full confession. But it has since been proven by Peruvian journalist Rosa Maria Palacios that this so-called cleaner is in fact a professional bodyguard and a long-serving member of Garcia’s security team.

These revelations have seriously embarrassed hospital authorities who collaborated with Garcia’s failed cover up. Garcia himself appears beyond embarrassment.

After all, this is the man who embezzled a fortune’s worth of public money and fled to France in disgrace after his first presidential term in the 80s, only to return to win the 2006 elections on the Popular American Revolutionary Alliance (APRA) ticket.

Officially a party of the workers, APRA — like the Australian Labor Party — has long since sold out to the big end of town, embracing pro-corporate policies.

Garcia’s previously unthinkable comeback was facilitated by generous campaign funding from US government sources, which financed a relentless propaganda campaign against his main opponent, left-leaning Ollanta Humala of the Peruvian Nationalist Party (PNP).

Galvez’s courageous stand appears to have been prompted by the latest scandal involving Garcia: vote rigging. It has been alleged that widespread electoral fraud has perverted the course of Lima’s October 3 mayoral elections.

Desperate to contain the rise of the new centre-left party Fuerza Social (FS), Garcia’s APRA machine reportedly intervened through the National Office of Electoral Processes (ONPU) to illegally disallow more than 8000 votes cast for FS candidate Susanna Villaran.

Polls were predicting a strong win for FS, which would have been the first left-of-centre victory in a race for mayor since 1986. Garcia’s manipulation worked in favour of the conservative establishment candidate Lourdes Flores, prompting protests by FS supporters.

In a highly suspicious development, the ONPU has released figures indicating a dramatic narrowing of Villaran’s previously comfortable lead.

At the time of writing, the result still hangs in the balance. Should Flores be declared the winner, few are in any doubt that it would represent one of the most brazen examples of electoral fraud in Peruvian history.

The support for FS is a sign of growing popular disenchantment with the neoliberal “free trade” policies pursued by successive US-backed right wing administrations. The ruling elite and its foreign backers are determined to stem the tide.

In a disturbing sign of rising repression and censorship, maverick journalist and writer Jaime Baily’s high-rating television show El Francotirador (“The Sniper”) has been abruptly axed by channel Frequencia Latina for denouncing the vote rigging scandal and for planning to interview Galvez.

Baily has won a popular following in Peru for daring to speak out against corrupt practices. Now it appears that he has gone too far for Frequencia Latina’s owner and director Baruch Ivcher, a member of the Peruvian oligarchy and a close associate of Garcia’s.

So much for freedom of speech in “democratic” and “investment-friendly” Peru, a country recently praised by US President Barack Obama as a model for the rest of the continent.

If Bolivian President Evo Morales, Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez or any other leader of the Latin American left were to conduct themselves this way, the international corporate media would immediately launch into a chorus of condemnation.

Along with the Colombian regime of war criminal Juan Santos, Garcia’s Peru is Washington’s strongest ally in the South American continent. This helps to explain why he can apparently get away with anything.

Garcia’s sordid accommodation to foreign capital has had a corrosive effect on Peruvian society, further undermining an already jaded faith in public institutions.

Public pressure forced Garcia to sack his entire cabinet in October 2008. Secret recordings had emerged of several senior government members discussing the bribes they would receive from a Norwegian oil company in return for Amazonian extraction rights.

Grassroots activist network Second Class Citizens, one of several dissident groups becoming increasingly active in Peru, said: “Our country is going through one of the gravest moral crises in its history.

“The poverty and exclusion of millions of Peruvians is being extended by institutionalised corruption and the capture of the state by private interests.

“This system based on the fire sale of the country’s assets, the destruction of our natural resources and the criminalisation of protest is fertile ground for the advancement of corruption…let’s reclaim our Peru.”

Ricardo Galvez’s act of defiance sums up the feelings of millions of Peruvians towards the rotten-to-the-core president who is a puppet dictator in all but name.

No one in Peru is seriously debating the substance of Galvez’s allegation because it is common knowledge in every quarter of the country that Alan Garcia is as corrupt as they come.

Tuesday 26 October 2010

Thursday 16 September 2010

U.S. Praise for Peru's Economy Misses the Mark

By Lisa Skeen

Republished from NACLA

Sep 13 2010 - The Peruvian economy has been enjoying something of a heyday lately, basking in the glow of the mainstream media. Currently being hailed as something of a Latin American wonder child, the Andean country has received increasing press coverage for its near decade of strong growth, which has continued despite the global economic downturn. But extensive coverage of fawning comments by President Obama have overshadowed the parallel narrative of a country potentially on the brink of disaster, with widespread voter discontent, sharp income disparity, and explosively divergent claims to land and resources.

After Peruvian president Alan García visited the White House early this summer, Obama praised the country during a press conference, stating “We've seen not only the solidification of a thriving democracy but also an extraordinary economic success story. Even over the last year in the midst of a very tough global recession, we saw that Peru was able to remain resilient.”

Meanwhile, outside the White House, a small group of activists protested the meeting. A Peruvian woman and her daughter were later charged with defacing government property after the daughter chained herself to a White House fence and the mother poured an oily substance on her.

The incident, which was meant to highlight the environmental destruction wrought by mining companies, was mentioned only in passing on an ABC news blog. Obama's “economic success story” line, however, has reverberated through the mainstream media.

His comments, however, are as much a statement of faith in neoliberal trade policies as they are a statement of faith in Peru itself.

Certainly, the Peruvian economy has expanded. In May, the International Monetary Fund estimated that Peru's economy would expand by 6.3% in 2010 – the largest increase in the western hemisphere – due mostly to foreign direct investment (FDI) in mining and energy and the soaring price of gold, Peru's second-biggest export. Bank of America estimated that investment in the country would nearly double in 2011, to $8.4 billion, from $4.4 billion in 2009.

And yet, García's approval ratings hover at around 31%, up slightly from an abysmal low of 26% in May. His ratings reflect the reality that there is often little, if any, immediate correlation between GDP growth and quality of life for ordinary citizens.

Former president Alejandro Toledo described an alternate reality in an interview with PBS Newshour: “[There are] millions of Amazonians, Afro-Peruvians, who don't have the chance to have access to potable water and sanitation, to quality health care . . . ,[and] access to energy. And that's a population that's very discontented, and today getting together.”

A June report by Oxfam America paints a bleak picture of Peru. Throughout the 1990s, reports Oxfam, the country underwent a dramatic restructuring, with heavy emphasis on decentralization. As a result, local governments are now given 50% of royalties and taxes paid by extractive industries (called the canon minero), which in theory, should have been a boon to local communities, given the rapid growth of FDI. FDI inflows have nearly tripled in the last decade, from $1 billion during 1990-1999 to $2.7 billion during 2000-2009. As in the rest of Latin America, the exploitation of natural resources, particularly minerals and gas, is responsible for the majority of this investment.

Poverty indices, however, indicate that foreign investment and the current system of royalty distribution – hobbled by lack of institutional support and corruption – is highly ineffective at spreading wealth equitably. The García administration claimed the national poverty rate fell from 48.7% in 2005 to 34.8% in 2009, but Farid Matuk, a former head of the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (INEI) – the organization responsible for these statistics - was highly critical of García's conclusions, which have been widely reprinted in the media. According to Matuk, “The poverty figures are not a product of scientific measurements but an artistic creation . . . there is no math on earth that backs up INEI's statistics.”

A closer look at INEI statistics indicates that poverty levels have actually increased in rural areas, particularly in rural areas associated with mining, agriculture exports, and the Amazon. They range from an astounding 70.3% in Apurimac to 56% in Cajamarca (Peru's leading gold mining region) to a low of 13.7% in the Pacific coast region of Ica. Food poverty levels, considered a more accurate indicator of day-to-day hardship, have increased in rural areas, from 40.7% in 2005 to 45.8% in 2010.

Mining and gas concessions cover a staggering 70% of the Peruvian Amazon, many of which overlap with indigenous lands. Though many of the concessions are not being actively utilized, forecasts about environmental degradation are grim One recently released study offered a worse-case prediction that 91% of the Amazon would be deforested/degraded by 2041.

Rural discontent over land use, which has been simmering for years, boiled over in June 2009 with indigenous protests against the granting of exploration concessions to oil and gas companies in Bagua. Thus far, the protests have had little effect on García's policies.

The potential for such deadly explosiveness has investors concerned that there is a “sizable danger” that Peru will elect a populist president in April 2011. The possibility is considered likely enough to warrant the suspension of anticipated credit ratings upgrades until after the elections.

The potential for the election of a president who appeals to the rural poor rather than the urban business class no doubt looms large in the minds of investors and U.S. officials. Under García, Peru has remained a critical ally of the United States, particularly for its strategic location among other coca-cultivating countries that are, at best, highly wary of U.S. foreign policy. The potential deepening of a military alliance between the two countries was alluded to in comments by U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates during an April visit to Lima.

But it is most likely Peru's friendliness to foreign investors that goes the farthest to explain Washington's insistent praise for Peru's “growth” amid such stark evidence of domestic discontent. The United States – Peru Trade Promotion Agreement (TPA) went into effect on February 1, 2009, and according to the U.S. Trade Representative, trade between the two countries grew to $9.1 billion in 2009, up from $3.6 billion in 1999.

The TPA included a requirement that Peru protect labor rights, as well as a pledge of bilateral cooperation on the promotion of environmental protection. Under the agreement, Peru had 18 months from the February 1 implementation date to bring itself into compliance with this pledge. In July of this year, U.S. Ambassador Ron Kirk, expressed concern that Peru would not meet these obligations by the August 1 deadline.

Thus far, the Obama administration has not seriously addressed Peru's noncompliance with those few parts of the agreement capable of positively impacting local communities. Meanwhile, the praise keeps flowing and foreign investors continue to profit as rural Peruvians sink deeper into poverty – and discontent.

Lisa Skeen is a NACLA Research Associate.

Republished from NACLA

Sep 13 2010 - The Peruvian economy has been enjoying something of a heyday lately, basking in the glow of the mainstream media. Currently being hailed as something of a Latin American wonder child, the Andean country has received increasing press coverage for its near decade of strong growth, which has continued despite the global economic downturn. But extensive coverage of fawning comments by President Obama have overshadowed the parallel narrative of a country potentially on the brink of disaster, with widespread voter discontent, sharp income disparity, and explosively divergent claims to land and resources.

After Peruvian president Alan García visited the White House early this summer, Obama praised the country during a press conference, stating “We've seen not only the solidification of a thriving democracy but also an extraordinary economic success story. Even over the last year in the midst of a very tough global recession, we saw that Peru was able to remain resilient.”

Meanwhile, outside the White House, a small group of activists protested the meeting. A Peruvian woman and her daughter were later charged with defacing government property after the daughter chained herself to a White House fence and the mother poured an oily substance on her.

The incident, which was meant to highlight the environmental destruction wrought by mining companies, was mentioned only in passing on an ABC news blog. Obama's “economic success story” line, however, has reverberated through the mainstream media.

His comments, however, are as much a statement of faith in neoliberal trade policies as they are a statement of faith in Peru itself.

Certainly, the Peruvian economy has expanded. In May, the International Monetary Fund estimated that Peru's economy would expand by 6.3% in 2010 – the largest increase in the western hemisphere – due mostly to foreign direct investment (FDI) in mining and energy and the soaring price of gold, Peru's second-biggest export. Bank of America estimated that investment in the country would nearly double in 2011, to $8.4 billion, from $4.4 billion in 2009.

And yet, García's approval ratings hover at around 31%, up slightly from an abysmal low of 26% in May. His ratings reflect the reality that there is often little, if any, immediate correlation between GDP growth and quality of life for ordinary citizens.

Former president Alejandro Toledo described an alternate reality in an interview with PBS Newshour: “[There are] millions of Amazonians, Afro-Peruvians, who don't have the chance to have access to potable water and sanitation, to quality health care . . . ,[and] access to energy. And that's a population that's very discontented, and today getting together.”

A June report by Oxfam America paints a bleak picture of Peru. Throughout the 1990s, reports Oxfam, the country underwent a dramatic restructuring, with heavy emphasis on decentralization. As a result, local governments are now given 50% of royalties and taxes paid by extractive industries (called the canon minero), which in theory, should have been a boon to local communities, given the rapid growth of FDI. FDI inflows have nearly tripled in the last decade, from $1 billion during 1990-1999 to $2.7 billion during 2000-2009. As in the rest of Latin America, the exploitation of natural resources, particularly minerals and gas, is responsible for the majority of this investment.

Poverty indices, however, indicate that foreign investment and the current system of royalty distribution – hobbled by lack of institutional support and corruption – is highly ineffective at spreading wealth equitably. The García administration claimed the national poverty rate fell from 48.7% in 2005 to 34.8% in 2009, but Farid Matuk, a former head of the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (INEI) – the organization responsible for these statistics - was highly critical of García's conclusions, which have been widely reprinted in the media. According to Matuk, “The poverty figures are not a product of scientific measurements but an artistic creation . . . there is no math on earth that backs up INEI's statistics.”

A closer look at INEI statistics indicates that poverty levels have actually increased in rural areas, particularly in rural areas associated with mining, agriculture exports, and the Amazon. They range from an astounding 70.3% in Apurimac to 56% in Cajamarca (Peru's leading gold mining region) to a low of 13.7% in the Pacific coast region of Ica. Food poverty levels, considered a more accurate indicator of day-to-day hardship, have increased in rural areas, from 40.7% in 2005 to 45.8% in 2010.

Mining and gas concessions cover a staggering 70% of the Peruvian Amazon, many of which overlap with indigenous lands. Though many of the concessions are not being actively utilized, forecasts about environmental degradation are grim One recently released study offered a worse-case prediction that 91% of the Amazon would be deforested/degraded by 2041.

Rural discontent over land use, which has been simmering for years, boiled over in June 2009 with indigenous protests against the granting of exploration concessions to oil and gas companies in Bagua. Thus far, the protests have had little effect on García's policies.

The potential for such deadly explosiveness has investors concerned that there is a “sizable danger” that Peru will elect a populist president in April 2011. The possibility is considered likely enough to warrant the suspension of anticipated credit ratings upgrades until after the elections.

The potential for the election of a president who appeals to the rural poor rather than the urban business class no doubt looms large in the minds of investors and U.S. officials. Under García, Peru has remained a critical ally of the United States, particularly for its strategic location among other coca-cultivating countries that are, at best, highly wary of U.S. foreign policy. The potential deepening of a military alliance between the two countries was alluded to in comments by U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates during an April visit to Lima.

But it is most likely Peru's friendliness to foreign investors that goes the farthest to explain Washington's insistent praise for Peru's “growth” amid such stark evidence of domestic discontent. The United States – Peru Trade Promotion Agreement (TPA) went into effect on February 1, 2009, and according to the U.S. Trade Representative, trade between the two countries grew to $9.1 billion in 2009, up from $3.6 billion in 1999.

The TPA included a requirement that Peru protect labor rights, as well as a pledge of bilateral cooperation on the promotion of environmental protection. Under the agreement, Peru had 18 months from the February 1 implementation date to bring itself into compliance with this pledge. In July of this year, U.S. Ambassador Ron Kirk, expressed concern that Peru would not meet these obligations by the August 1 deadline.

Thus far, the Obama administration has not seriously addressed Peru's noncompliance with those few parts of the agreement capable of positively impacting local communities. Meanwhile, the praise keeps flowing and foreign investors continue to profit as rural Peruvians sink deeper into poverty – and discontent.

Lisa Skeen is a NACLA Research Associate.

Thursday 2 September 2010

El buen vivir: Peruvian Indigenous Leader Mario Palacios

By Deborah Poole

In 1999, community leaders representing more than 1,200 communities in nine regions of Peru came together to form the National Confederation of Communities Affected by Mining (CONACAMI). Founded to counter the negative environmental and social impact of mining and the virtual absence of state regulation, CONACAMI initially sought direct, bilateral dialogue with the mining companies. But at its second national congress in 2003, delegates voted to reject dialogue and to embrace an anti-systemic politics that calls for the total rejection of mining and the neoliberal economy’s exclusionary practices and principles. They also voted to reconstitute CONACAMI as an indigenous confederation that would center its demands on defending indigenous rights, promoting indigenous political participation, and refounding the nation-state. In subsequent years, CONACAMI has expanded its presence in the Andean region through the Andean Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations (CAOI), an umbrella organization that CONACAMI helped to found in 2006.

The history of CONACAMI and its importance to popular struggles in the Andes points to the centrality of both community and Mother Earth to indigenous proposals for rethinking politics and the state. In this respect, it is also significant that CONACAMI, as an organization founded in opposition to the untrammeled destruction of the environment and natural resources, has played such an important role in revitalizing indigenous political organizations in the Andean regions of Peru, where self-ascribed indigenous organizations have not historically played as visible a role as either peasant or labor movements in popular political resistance.

In May, Deborah Poole interviewed Mario Palacios, president of CONACAMI (2008–10), in New York. In the edited transcript that follows, Palacios expands on the political and cultural vision of CONACAMI and its relationships with other indigenous organizations, including AIDESEP, the Peruvian Amazonian confederation that led the indigenous uprisings of 2008 and 2009.

CONACAMI is composed of communities from the Peruvian Andes that have suffered from the chaotic and disorderly expansion of mining in recent years. In Peru, mining is a crucial activity for the government in that it represents 64% of the country’s exports. However, although the state celebrates mining as an activity that is crucial for maintaining exports, it never talks about the negative effects that mining has on our lives. Mining generates not only environmental contamination but also greater poverty; it affects social relations within communities; and it leads, in many cases, to the actual disintegration of communities. It also jeopardizes resources that are necessary for the development of communities, like water and land, by degrading or contaminating them. Faced with this, CONACAMI is responding as an organization to defend our territories and the natural resources of Peru.

CONACAMI is basically an organization of communities that works in 16 of the country’s 24 departments. There are around 6,000 communities in Peru, of which 3,200 suffer the negative effects of mining. CONACAMI has almost 2,000 Andean community affiliates. Beyond that, however our work also draws on the diversity of Peru’s social movement. For example, we are constructing a strong alliance, a process of unity with indigenous organizations from the Peruvian Amazon. In this sense, CONACAMI and the Inter-Ethnic Development Association of the Peruvian Rainforest (AIDESEP) are organizations that have led the struggle in both the Andes and the Amazon. We greatly respect the work of AIDESEP, an organization that has been carrying on very effective work in the Amazon since the early 1980s. In the Peruvian Andes, however, indigenous political organizing is more recent.

Peru’s neoliberal political process bases its economy on extractive industries. This political process brings not only the “free market,” but also free access to natural resources, free investment, and above all the looting of our resources. So our ancestral communities, many of which have territorial titles that date back 300 or 400 years to the colonial period, are today suffering from the expropriation, dispossession, and dissolution of their territories, not only because of the actions of the mining companies, but also because of the state itself and the governmental policies that are being applied in Peru. This is a politics of expropriation that dissolves or liquidates communities. And within this politics of extermination of communities, the rights of ancestral, originary, or indigenous peoples are not recognized.

In these last years, however, as a result of pressure, struggle, and resistance from both Andean and Amazonian communities, the Peruvian state has recognized the existence of the International Labor Organization Convention 169 (ILO 169). Although Peru signed this international convention 15 years ago, the state has continued to deny us our rights, as indigenous peoples, in every conceivable way. But the indigenous struggle has finally forced the state to recognize that this convention does have normative value as a binding international convention. It was the indigenous uprisings of 2008 and 2009 that forced the state to recognize these rights.

Today in Peru we are debating a legislative proposal that would implement our right to prior consultation, as provided for in the text of ILO 169.1 They are also debating a Law of Indigenous Peoples. I think these are important elements to achieve the recognition of indigenous rights in Peru, because these are rights that have been dismissed or denied ever since our lands were first invaded and colonized. But the proposal put forward by CONACAMI and the indigenous movements goes well beyond this question of rights and the defense of our own territories and natural resources. We are fighting because humanity itself is lost in a way of life that is marked by forms of accumulation and by the destruction and contamination of Mother Earth. These tendencies have increased in recent years because neoliberal capitalism is putting humanity’s very survival at risk. In Peru, for example, we are experiencing in a particularly dramatic way the effects of global climate change.

For us, it is not just climate change, but rather a climatic crisis that manifests itself in the frosts, hailstorms, torrential rains, droughts, floods, and landslides that we are enduring in the Andean region. These climatic changes, which reduce agricultural production and introduce new diseases that we never before knew, are directly affecting our way of life. Humanity must think carefully if we are to avoid in the next decades a crisis that could lead to our own extinction. The indigenous movement has taken up this challenge to construct, during the past 20 years, a political proposal that is also a proposal for life, a project of life—el buen vivir. This project, which translates in Quechua as allin kawsay or in Aymara as sumah qamana, is composed of various parts: It encompasses a new vision, a new way of seeing, that is different from Western developmentalism in that we call for harmony with, and respect for, Mother Earth.2

Our project also calls for another way of conceiving the state. The republican states that were invented 200 years ago are effectively exhausted, since have not been able to resolve fundamental problems. These homogenizing, uninational, monocultural, monolingual states, which took shape in the aftermath of the French Revolution, are today in crisis. In Peru, for example, we are effectively excluded from social, political, and economic participation because the state is dominated by criollos who are, in fact, a minority in the country. So the indigenous movement has put forward the need to reinvent another form of the state and a new model of democracy—a democracy that is no longer just representative. In the Peruvian case, representational democracy, through the Congress, has effectively collapsed. The Congress is highly corrupt, inefficient, and informal. The executive branch is also characterized by high levels of corruption. So we need a different democracy, and the form of democracy that we propose from within the indigenous movements is communitarian; it is a participatory democracy of mandar obedeciendo.3

1. On May 19, the Peruvian legislature passed the Law of Prior Consultation to implement rights guaranteed in ILO 169. President García refused to sign the bill, arguing that indigenous communities are not juridically recognized subjects and that the law would give indigenous peoples “veto power” over the nation’s development initiatives. The government’s actions, which were supported by Peru’s Constitutional Commission on July 15, have met with vigorous opposition from indigenous organizations, including CONACAMI, as well as from the Peruvian Ombudsmen (Defensoría del Pueblo).

2. The literal translation of allin kawsay is “to live well.” However, the term is understood and used in a much broader sense by indigenous political organizations and activists, who use it to refer to the practices of living in harmony with nature, with other communities, and within families and communities. As such, it refers as much to the practice of equality and ethical responsibility as to the aspiration of achieving a more just world.

3. Mandar obediciendo is a Zapatista phrase that has gained wide currency in indigenous movements in Latin America to refer to practices of democratic consultation in which authorities or elected representatives “lead by obeying.” In this view of political authority, leaders do not have the authority to make decisions without both consulting their bases and taking all opinions into account.

Deborah Poole is Professor of Anthropology at Johns Hopkins University. Her recent publications include A Blackwell Companion to Latin American Anthropology (Blackwell, 2008).

Republished from NACLA

In 1999, community leaders representing more than 1,200 communities in nine regions of Peru came together to form the National Confederation of Communities Affected by Mining (CONACAMI). Founded to counter the negative environmental and social impact of mining and the virtual absence of state regulation, CONACAMI initially sought direct, bilateral dialogue with the mining companies. But at its second national congress in 2003, delegates voted to reject dialogue and to embrace an anti-systemic politics that calls for the total rejection of mining and the neoliberal economy’s exclusionary practices and principles. They also voted to reconstitute CONACAMI as an indigenous confederation that would center its demands on defending indigenous rights, promoting indigenous political participation, and refounding the nation-state. In subsequent years, CONACAMI has expanded its presence in the Andean region through the Andean Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations (CAOI), an umbrella organization that CONACAMI helped to found in 2006.

The history of CONACAMI and its importance to popular struggles in the Andes points to the centrality of both community and Mother Earth to indigenous proposals for rethinking politics and the state. In this respect, it is also significant that CONACAMI, as an organization founded in opposition to the untrammeled destruction of the environment and natural resources, has played such an important role in revitalizing indigenous political organizations in the Andean regions of Peru, where self-ascribed indigenous organizations have not historically played as visible a role as either peasant or labor movements in popular political resistance.

In May, Deborah Poole interviewed Mario Palacios, president of CONACAMI (2008–10), in New York. In the edited transcript that follows, Palacios expands on the political and cultural vision of CONACAMI and its relationships with other indigenous organizations, including AIDESEP, the Peruvian Amazonian confederation that led the indigenous uprisings of 2008 and 2009.

CONACAMI is composed of communities from the Peruvian Andes that have suffered from the chaotic and disorderly expansion of mining in recent years. In Peru, mining is a crucial activity for the government in that it represents 64% of the country’s exports. However, although the state celebrates mining as an activity that is crucial for maintaining exports, it never talks about the negative effects that mining has on our lives. Mining generates not only environmental contamination but also greater poverty; it affects social relations within communities; and it leads, in many cases, to the actual disintegration of communities. It also jeopardizes resources that are necessary for the development of communities, like water and land, by degrading or contaminating them. Faced with this, CONACAMI is responding as an organization to defend our territories and the natural resources of Peru.

CONACAMI is basically an organization of communities that works in 16 of the country’s 24 departments. There are around 6,000 communities in Peru, of which 3,200 suffer the negative effects of mining. CONACAMI has almost 2,000 Andean community affiliates. Beyond that, however our work also draws on the diversity of Peru’s social movement. For example, we are constructing a strong alliance, a process of unity with indigenous organizations from the Peruvian Amazon. In this sense, CONACAMI and the Inter-Ethnic Development Association of the Peruvian Rainforest (AIDESEP) are organizations that have led the struggle in both the Andes and the Amazon. We greatly respect the work of AIDESEP, an organization that has been carrying on very effective work in the Amazon since the early 1980s. In the Peruvian Andes, however, indigenous political organizing is more recent.

Peru’s neoliberal political process bases its economy on extractive industries. This political process brings not only the “free market,” but also free access to natural resources, free investment, and above all the looting of our resources. So our ancestral communities, many of which have territorial titles that date back 300 or 400 years to the colonial period, are today suffering from the expropriation, dispossession, and dissolution of their territories, not only because of the actions of the mining companies, but also because of the state itself and the governmental policies that are being applied in Peru. This is a politics of expropriation that dissolves or liquidates communities. And within this politics of extermination of communities, the rights of ancestral, originary, or indigenous peoples are not recognized.

In these last years, however, as a result of pressure, struggle, and resistance from both Andean and Amazonian communities, the Peruvian state has recognized the existence of the International Labor Organization Convention 169 (ILO 169). Although Peru signed this international convention 15 years ago, the state has continued to deny us our rights, as indigenous peoples, in every conceivable way. But the indigenous struggle has finally forced the state to recognize that this convention does have normative value as a binding international convention. It was the indigenous uprisings of 2008 and 2009 that forced the state to recognize these rights.

Today in Peru we are debating a legislative proposal that would implement our right to prior consultation, as provided for in the text of ILO 169.1 They are also debating a Law of Indigenous Peoples. I think these are important elements to achieve the recognition of indigenous rights in Peru, because these are rights that have been dismissed or denied ever since our lands were first invaded and colonized. But the proposal put forward by CONACAMI and the indigenous movements goes well beyond this question of rights and the defense of our own territories and natural resources. We are fighting because humanity itself is lost in a way of life that is marked by forms of accumulation and by the destruction and contamination of Mother Earth. These tendencies have increased in recent years because neoliberal capitalism is putting humanity’s very survival at risk. In Peru, for example, we are experiencing in a particularly dramatic way the effects of global climate change.

For us, it is not just climate change, but rather a climatic crisis that manifests itself in the frosts, hailstorms, torrential rains, droughts, floods, and landslides that we are enduring in the Andean region. These climatic changes, which reduce agricultural production and introduce new diseases that we never before knew, are directly affecting our way of life. Humanity must think carefully if we are to avoid in the next decades a crisis that could lead to our own extinction. The indigenous movement has taken up this challenge to construct, during the past 20 years, a political proposal that is also a proposal for life, a project of life—el buen vivir. This project, which translates in Quechua as allin kawsay or in Aymara as sumah qamana, is composed of various parts: It encompasses a new vision, a new way of seeing, that is different from Western developmentalism in that we call for harmony with, and respect for, Mother Earth.2

Our project also calls for another way of conceiving the state. The republican states that were invented 200 years ago are effectively exhausted, since have not been able to resolve fundamental problems. These homogenizing, uninational, monocultural, monolingual states, which took shape in the aftermath of the French Revolution, are today in crisis. In Peru, for example, we are effectively excluded from social, political, and economic participation because the state is dominated by criollos who are, in fact, a minority in the country. So the indigenous movement has put forward the need to reinvent another form of the state and a new model of democracy—a democracy that is no longer just representative. In the Peruvian case, representational democracy, through the Congress, has effectively collapsed. The Congress is highly corrupt, inefficient, and informal. The executive branch is also characterized by high levels of corruption. So we need a different democracy, and the form of democracy that we propose from within the indigenous movements is communitarian; it is a participatory democracy of mandar obedeciendo.3

1. On May 19, the Peruvian legislature passed the Law of Prior Consultation to implement rights guaranteed in ILO 169. President García refused to sign the bill, arguing that indigenous communities are not juridically recognized subjects and that the law would give indigenous peoples “veto power” over the nation’s development initiatives. The government’s actions, which were supported by Peru’s Constitutional Commission on July 15, have met with vigorous opposition from indigenous organizations, including CONACAMI, as well as from the Peruvian Ombudsmen (Defensoría del Pueblo).

2. The literal translation of allin kawsay is “to live well.” However, the term is understood and used in a much broader sense by indigenous political organizations and activists, who use it to refer to the practices of living in harmony with nature, with other communities, and within families and communities. As such, it refers as much to the practice of equality and ethical responsibility as to the aspiration of achieving a more just world.

3. Mandar obediciendo is a Zapatista phrase that has gained wide currency in indigenous movements in Latin America to refer to practices of democratic consultation in which authorities or elected representatives “lead by obeying.” In this view of political authority, leaders do not have the authority to make decisions without both consulting their bases and taking all opinions into account.

Deborah Poole is Professor of Anthropology at Johns Hopkins University. Her recent publications include A Blackwell Companion to Latin American Anthropology (Blackwell, 2008).

Republished from NACLA

Extractivism Spills Death and Destruction in Peru

By Deborah Poole and Gerardo Rénique

On June 19, a barge belonging to the Argentine transnational Pluspetrol spilled 400 barrels of oil into the Maranon River in Peru’s northeastern Loreto department. The day after the spill, the Peruvian government’s Bioactive Substances Laboratory tested the river water—which the Cocama and Achuar peoples depend upon for both water and fish—and found very high levels of oil. “It was practically all petroleum,” said chemical engineer Víctor Sotero, of the government’s Peruvian Amazon Research Institute.1

Even though the extensive contamination had been reported to the central government, Minister of Energy and Mines Pedro Sánchez seemed to suggest that the many lives and the complex environmental systems it had destroyed were not important, when he declared on national television that the Marañon spill involved a “very small amount of oil.” When “compared with what has happened in the Gulf of Mexico,” he concluded, “it should not be a cause for alarm.”2

The Marañon spill was certainly much smaller in absolute terms than the estimated 35,000 to 60,000 barrels of crude oil that British Petroleum dumped each day into the Gulf of Mexico for almost three months.3 But scale is not an issue in environmental disasters that destroy complex ecological and riverine systems, and deprive the humans who depend on those environments for food, water, and a future for their communities. Sánchez’s comparison does, however, speak clearly of the Peruvian government’s attitude that environmental disasters are acceptable collateral damage for the millions of dollars that mining generates for Peru’s elite.

Indeed, the Marañon spill was just the latest example in a long series of environmental disasters that have accompanied Peru’s boom in mining, logging, and oil. Less than one week after the Marañon spill, the Caudalosa Chica company’s zinc and lead mine in the southern region of Huancavelica dumped more than 550 tons of tailings containing cyanide, arsenic, and lead into rivers that provide the sole source of drinking and irrigation water for more than 40,000 Peruvians.4 Again, the government of President Alan García responded with a series of denials, dismissals, and disclaimers.

One of the biggest challenges facing indigenous peoples in Peru, and throughout the Americas, is the unregulated expansion of these industries and the resulting contamination of land and water. The García government has granted oil, lumber, and mining companies territorial concessions and leases to almost 75% of the Peruvian Amazon. Of these, the vast majority (58 out of 64 leases) are located in indigenous territories. García’s government has also refused to implement rights of prior consultation—or any of the many other rights accorded to indigenous peoples in International Labor Organization Convention 169, which Peru ratified in 1993 and signed into law in 1994.

Because natural-resource extraction directly affects both nature itself and those forms of community and social life that seek harmony with the earth, it has served as a catalyst for the emergence of radical indigenous politics grounded in the defense of nature and life. Indigenous Peruvians have taken the lead in denouncing the mining, logging, and oil companies, as well as Peruvian government policies that promote extractive economies while trampling the rights of local communities and populations. In response, indigenous communities have mobilized to resist laws and policies that support the further incursion of mining companies. These include laws that grant the state ownership of subsoil resources in indigenous and peasant communities, laws that give the state the right to grant concessions without compensation, and policies that call for the titling and privatization (“regularization”) of collectively held lands in peasant and indigenous communities.

Indigenous organizations—including the Inter-Ethnic Development Association of the Peruvian Rainforest (AIDESEP), the Andean Coordinating Committee of Indigenous Organizations (CAOI), and the National Federation of Communities Affected by Mining (CONACAMI)—have called for criminal charges to be brought against companies like Caudalosa Chica and Pluspetrol. Faced with continuing protests from indigenous and regional leaders over the Caudalosa Chica disaster, the government finally imposed a symbolic fine on the mining company. The fine comes nowhere close to compensating for the extensive environmental and economic damages—and it will no doubt join the long list of environmental penalties that the García government has levied yet failed to collect. In the three years leading up to these two most recent environmental disasters, Peru has managed to collect only $4.4 million of the $20 million in environmental fines it had imposed on the largest mining companies, which made more than $20 billion in profits from Peruvian mines between 2005 and 2009.5 As a result, mining and petroleum companies continue to operate in a de facto state of impunity in Peru.

This and other serious challenges remain for Peruvian indigenous movements, despite their significant advances over the years. The neoliberal agenda allows no room for negotiating territorial or political rights, and the entrenched racism of Latin America’s dominant criollo or mestizo societies makes it difficult for indigenous perspectives and voices to be heard. The García government has systematically criminalized indigenous organizations, and demonized indigenous peoples in speeches and TV spots that portray Indians who defend the environment and their territorial rights as “manger dogs,” “subversives,” and “savages.”

Indigenous organizations have made common cause with political actors who do not necessarily identify as indigenous but share their concerns. On July 7 and 8, for example, indigenous leaders joined opposition political representatives from Huancavelica to lead a regional strike and a “sacrifice march” to Lima to protest the García government’s refusal to act in the Caudalosa Chica case. Only after a general regional strike, marches, and protests of indigenous and popular organizations, and an increasing critical media, did the government reluctantly agree to temporarily close the mine.6

1. Quoted in Milagros Salazar, “Don’t Minimize Impacts of Amazon Oil Spill,”

Inter Press Service, July 1, 2010.

2. Iván Herrera Gálvez, “Perú: el mito de la petrolera ‘limpia y responsible’ se hunde en la oleosa realidad,” Servicios en Comunicación Intercultural Servindi (servindi.org; Lima, Peru), June 30, 2010.

3. CNN.com, “Oil Estimate Raised to 35,000–60,000 Barrels a Day,” July 16, 2010.

4. Servicios en Comunicación Intercultural Servindi, “Peru: Denuncian atentado criminal a la ecologia de los rios Totora y Opamayo,” June 28, 2010.

5. Milagros Salazar, “La impotente regulación,” IDL-Reporteros.pe, June 3, 2010.

6. La República (Lima), “Ordenan paralizar operaciones de mina Caudalosa Chica,” July 13, 2010.

Deborah Poole is Professor of Anthropology at Johns Hopkins University. Her recent publications include A Blackwell Companion to Latin American Anthropology (Blackwell, 2008). Gerardo Rénique is Associate Professor of history at City College, City University of New York. Republished from NACLA

On June 19, a barge belonging to the Argentine transnational Pluspetrol spilled 400 barrels of oil into the Maranon River in Peru’s northeastern Loreto department. The day after the spill, the Peruvian government’s Bioactive Substances Laboratory tested the river water—which the Cocama and Achuar peoples depend upon for both water and fish—and found very high levels of oil. “It was practically all petroleum,” said chemical engineer Víctor Sotero, of the government’s Peruvian Amazon Research Institute.1

Even though the extensive contamination had been reported to the central government, Minister of Energy and Mines Pedro Sánchez seemed to suggest that the many lives and the complex environmental systems it had destroyed were not important, when he declared on national television that the Marañon spill involved a “very small amount of oil.” When “compared with what has happened in the Gulf of Mexico,” he concluded, “it should not be a cause for alarm.”2

The Marañon spill was certainly much smaller in absolute terms than the estimated 35,000 to 60,000 barrels of crude oil that British Petroleum dumped each day into the Gulf of Mexico for almost three months.3 But scale is not an issue in environmental disasters that destroy complex ecological and riverine systems, and deprive the humans who depend on those environments for food, water, and a future for their communities. Sánchez’s comparison does, however, speak clearly of the Peruvian government’s attitude that environmental disasters are acceptable collateral damage for the millions of dollars that mining generates for Peru’s elite.

Indeed, the Marañon spill was just the latest example in a long series of environmental disasters that have accompanied Peru’s boom in mining, logging, and oil. Less than one week after the Marañon spill, the Caudalosa Chica company’s zinc and lead mine in the southern region of Huancavelica dumped more than 550 tons of tailings containing cyanide, arsenic, and lead into rivers that provide the sole source of drinking and irrigation water for more than 40,000 Peruvians.4 Again, the government of President Alan García responded with a series of denials, dismissals, and disclaimers.

One of the biggest challenges facing indigenous peoples in Peru, and throughout the Americas, is the unregulated expansion of these industries and the resulting contamination of land and water. The García government has granted oil, lumber, and mining companies territorial concessions and leases to almost 75% of the Peruvian Amazon. Of these, the vast majority (58 out of 64 leases) are located in indigenous territories. García’s government has also refused to implement rights of prior consultation—or any of the many other rights accorded to indigenous peoples in International Labor Organization Convention 169, which Peru ratified in 1993 and signed into law in 1994.

Because natural-resource extraction directly affects both nature itself and those forms of community and social life that seek harmony with the earth, it has served as a catalyst for the emergence of radical indigenous politics grounded in the defense of nature and life. Indigenous Peruvians have taken the lead in denouncing the mining, logging, and oil companies, as well as Peruvian government policies that promote extractive economies while trampling the rights of local communities and populations. In response, indigenous communities have mobilized to resist laws and policies that support the further incursion of mining companies. These include laws that grant the state ownership of subsoil resources in indigenous and peasant communities, laws that give the state the right to grant concessions without compensation, and policies that call for the titling and privatization (“regularization”) of collectively held lands in peasant and indigenous communities.

Indigenous organizations—including the Inter-Ethnic Development Association of the Peruvian Rainforest (AIDESEP), the Andean Coordinating Committee of Indigenous Organizations (CAOI), and the National Federation of Communities Affected by Mining (CONACAMI)—have called for criminal charges to be brought against companies like Caudalosa Chica and Pluspetrol. Faced with continuing protests from indigenous and regional leaders over the Caudalosa Chica disaster, the government finally imposed a symbolic fine on the mining company. The fine comes nowhere close to compensating for the extensive environmental and economic damages—and it will no doubt join the long list of environmental penalties that the García government has levied yet failed to collect. In the three years leading up to these two most recent environmental disasters, Peru has managed to collect only $4.4 million of the $20 million in environmental fines it had imposed on the largest mining companies, which made more than $20 billion in profits from Peruvian mines between 2005 and 2009.5 As a result, mining and petroleum companies continue to operate in a de facto state of impunity in Peru.

This and other serious challenges remain for Peruvian indigenous movements, despite their significant advances over the years. The neoliberal agenda allows no room for negotiating territorial or political rights, and the entrenched racism of Latin America’s dominant criollo or mestizo societies makes it difficult for indigenous perspectives and voices to be heard. The García government has systematically criminalized indigenous organizations, and demonized indigenous peoples in speeches and TV spots that portray Indians who defend the environment and their territorial rights as “manger dogs,” “subversives,” and “savages.”

Indigenous organizations have made common cause with political actors who do not necessarily identify as indigenous but share their concerns. On July 7 and 8, for example, indigenous leaders joined opposition political representatives from Huancavelica to lead a regional strike and a “sacrifice march” to Lima to protest the García government’s refusal to act in the Caudalosa Chica case. Only after a general regional strike, marches, and protests of indigenous and popular organizations, and an increasing critical media, did the government reluctantly agree to temporarily close the mine.6

1. Quoted in Milagros Salazar, “Don’t Minimize Impacts of Amazon Oil Spill,”

Inter Press Service, July 1, 2010.

2. Iván Herrera Gálvez, “Perú: el mito de la petrolera ‘limpia y responsible’ se hunde en la oleosa realidad,” Servicios en Comunicación Intercultural Servindi (servindi.org; Lima, Peru), June 30, 2010.

3. CNN.com, “Oil Estimate Raised to 35,000–60,000 Barrels a Day,” July 16, 2010.

4. Servicios en Comunicación Intercultural Servindi, “Peru: Denuncian atentado criminal a la ecologia de los rios Totora y Opamayo,” June 28, 2010.

5. Milagros Salazar, “La impotente regulación,” IDL-Reporteros.pe, June 3, 2010.

6. La República (Lima), “Ordenan paralizar operaciones de mina Caudalosa Chica,” July 13, 2010.

Deborah Poole is Professor of Anthropology at Johns Hopkins University. Her recent publications include A Blackwell Companion to Latin American Anthropology (Blackwell, 2008). Gerardo Rénique is Associate Professor of history at City College, City University of New York. Republished from NACLA

Tuesday 31 August 2010

Peru: Amazon indigenous create new political party

Saturday, August 28, 2010

By Kiraz Janicke

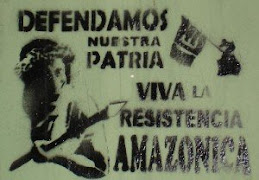

Peru’s Amazonian indigenous people have announced the creation of their own political party and will contest the presidential elections in April 2011.

The indigenous people clashed with Peruvian President Alan Garcia’s government in 2009 to defend their ancestral lands in the largest indigenous uprising in recent history.

The Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Jungle (AIDESEP), Peru’s largest and most representative indigenous organisation, announced the formation of the Alliance for an Alternative for Humanity party (Alianza para la Alternativa de la Humanidad — APHU).

The announcement came shortly after the one-year anniversary of Garcia’s violent crackdown on thousands of indigenous protesters near the town of Bagua Grande on June 5, 2009.

Indigenous communities were protesting against a series of government decrees in line with the US-Peru Free Trade-Agreement that opened up their ancestral lands to exploitation by oil, mining, timber and agribusiness companies and undermined constitutionally recognised consultation processes.

The Bagua massacre — as the crackdown became known — left at least 34 dead, including police and protesters, and unknown numbers of indigenous people disappeared. Bagua sparked national and international condemnation.

AIDESEP president Alberto Pizango — despite not being present at the Bagua protests — was charged with “conspiracy, sedition and rebellion” and was forced to flee the country and seek asylum in Nicaragua.

The crisis caused the entire ministerial cabinet to resign and forced the government to repeal some of its most controversial decrees.

But indigenous activists say the government is still illegally auctioning exploration licenses in the Amazon, without consultation or agreement from indigenous communities.

Political persecution of indigenous leaders continues. In November 2009, the Ministry of Justice issued a request to dissolve AIDESEP, but promptly backed away when the move sparked a public backlash.

The government has also tried to create alternatives to AIDESEP that agree with its neoliberal agenda, and to promote fake “consultation” processes with indigenous communities to ensure outcomes that favour transnational companies.

Pizango, who returned to Peru on May 26 to fight the government’s trumped up charges and spoke at the August 11 press conference, condemned the government’s attempt to divide the indigenous movement.

The new party was created by indigenous people but it will “attempt to embrace all the citizens of Peru who defend the forests, nature and life on Earth”, he said.

The party’s platform is based on three main points: peace, sovereignty and land rights; education and health for all Peruvians; and the indigenous concept of vivir bien (living well), which Pizango described as harmony between people and nature.

Pizango said the APHU “will be a political tool for defending the Amazon and its resources which belong to all Peruvians, who must be consulted about its fate”.

Pizango said he was willing to stand as APHU’s presidential candidate but said the traditional Apus, or indigenous leaders of the Amazon, would decide.

The party is in the process of collecting the required 160,000 signatures for official registration. So far it has 100,000 registered members.

Some have described Pizango as “Peru’s Evo Morales”. Morales is Bolivia’s first indigenous president who came to prominence by leading social struggles in the defence of natural resources and the rights of indigenous peoples.

Pizango said his project, like that of the Bolivian indigenous leader, is based on the “aspirations of peoples”.

“People are coming together today to defend planet Earth, to defend their right to a life of dignity whereby they can recover knowledge that allows them to live in harmony with nature and thereby ensure the survival of future generations.”

Peru has the second-largest indigenous population in South America after Bolivia. About 53% being of Peruvians are indigenous.

The new party is based primarily in rural areas and is made up of the poorest of the poor — Peru’s tribal indigenous communities — and for these reasons faces many challenges in terms of resources.

It is unlikely Pizango will be elected in 2011, but analyst Roger Rumrrill told AFP on August 11 that the creation of APHU is a good strategy “as an exercise in building power for the long term”.

Another candidate on the left is Marco Arana, priest and leader of the Peru Land and Freedom Movement. It describes itself as a “political movement that believes in social transformation via social movements”, and calls for the democratisation of power “in all spaces and at all levels”.

But the most visible face of the opposition in Peru is Ollanta Humala, leftist leader of the Peruvian Nationalist Party (PNP), who narrowly lost to Garcia in 2006.

All three candidates are fierce critics of neoliberal policies, but face an array of conservative or centrist politicians backed by the US and Peru’s traditional capitalist elites.

Republished from Green Left Weekly

By Kiraz Janicke

Peru’s Amazonian indigenous people have announced the creation of their own political party and will contest the presidential elections in April 2011.

The indigenous people clashed with Peruvian President Alan Garcia’s government in 2009 to defend their ancestral lands in the largest indigenous uprising in recent history.

The Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Jungle (AIDESEP), Peru’s largest and most representative indigenous organisation, announced the formation of the Alliance for an Alternative for Humanity party (Alianza para la Alternativa de la Humanidad — APHU).

The announcement came shortly after the one-year anniversary of Garcia’s violent crackdown on thousands of indigenous protesters near the town of Bagua Grande on June 5, 2009.

Indigenous communities were protesting against a series of government decrees in line with the US-Peru Free Trade-Agreement that opened up their ancestral lands to exploitation by oil, mining, timber and agribusiness companies and undermined constitutionally recognised consultation processes.

The Bagua massacre — as the crackdown became known — left at least 34 dead, including police and protesters, and unknown numbers of indigenous people disappeared. Bagua sparked national and international condemnation.

AIDESEP president Alberto Pizango — despite not being present at the Bagua protests — was charged with “conspiracy, sedition and rebellion” and was forced to flee the country and seek asylum in Nicaragua.

The crisis caused the entire ministerial cabinet to resign and forced the government to repeal some of its most controversial decrees.

But indigenous activists say the government is still illegally auctioning exploration licenses in the Amazon, without consultation or agreement from indigenous communities.

Political persecution of indigenous leaders continues. In November 2009, the Ministry of Justice issued a request to dissolve AIDESEP, but promptly backed away when the move sparked a public backlash.

The government has also tried to create alternatives to AIDESEP that agree with its neoliberal agenda, and to promote fake “consultation” processes with indigenous communities to ensure outcomes that favour transnational companies.

Pizango, who returned to Peru on May 26 to fight the government’s trumped up charges and spoke at the August 11 press conference, condemned the government’s attempt to divide the indigenous movement.

The new party was created by indigenous people but it will “attempt to embrace all the citizens of Peru who defend the forests, nature and life on Earth”, he said.

The party’s platform is based on three main points: peace, sovereignty and land rights; education and health for all Peruvians; and the indigenous concept of vivir bien (living well), which Pizango described as harmony between people and nature.

Pizango said the APHU “will be a political tool for defending the Amazon and its resources which belong to all Peruvians, who must be consulted about its fate”.

Pizango said he was willing to stand as APHU’s presidential candidate but said the traditional Apus, or indigenous leaders of the Amazon, would decide.

The party is in the process of collecting the required 160,000 signatures for official registration. So far it has 100,000 registered members.

Some have described Pizango as “Peru’s Evo Morales”. Morales is Bolivia’s first indigenous president who came to prominence by leading social struggles in the defence of natural resources and the rights of indigenous peoples.

Pizango said his project, like that of the Bolivian indigenous leader, is based on the “aspirations of peoples”.

“People are coming together today to defend planet Earth, to defend their right to a life of dignity whereby they can recover knowledge that allows them to live in harmony with nature and thereby ensure the survival of future generations.”

Peru has the second-largest indigenous population in South America after Bolivia. About 53% being of Peruvians are indigenous.

The new party is based primarily in rural areas and is made up of the poorest of the poor — Peru’s tribal indigenous communities — and for these reasons faces many challenges in terms of resources.

It is unlikely Pizango will be elected in 2011, but analyst Roger Rumrrill told AFP on August 11 that the creation of APHU is a good strategy “as an exercise in building power for the long term”.

Another candidate on the left is Marco Arana, priest and leader of the Peru Land and Freedom Movement. It describes itself as a “political movement that believes in social transformation via social movements”, and calls for the democratisation of power “in all spaces and at all levels”.

But the most visible face of the opposition in Peru is Ollanta Humala, leftist leader of the Peruvian Nationalist Party (PNP), who narrowly lost to Garcia in 2006.

All three candidates are fierce critics of neoliberal policies, but face an array of conservative or centrist politicians backed by the US and Peru’s traditional capitalist elites.

Republished from Green Left Weekly

Thursday 19 August 2010

US Activist Lori Berenson and Baby Son Returned to Peruvian Prison Just 3 Months After Release on Parole

US activist Lori Berenson has been sent back to a Peruvian prison just three months after she was freed on parole. Berenson had served nearly fifteen years following her 1996 conviction for collaborating with the rebel group the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement, or MRTA. Democracy Now interviews Lori Berenson’s mother, Rhoda Berenson in Lima, Peru. [transcript below]

JUAN GONZALEZ: We begin today’s show in Peru, where a three-judge panel has ordered the American activist Lori Berenson back to prison to serve the remaining five years of her twenty-year sentence. Berenson and her fifteen-month-old son Salvador had been free since May, when she was released on parole.

Berenson is the American activist who was arrested in 1995 in Lima, accused of collaborating with the rebel group Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement, or MRTA. She was initially sentenced to life in prison for treason, but four-and-a-half years later, due to international pressure, her sentence was vacated. She was retried by a civilian court, which reduced her sentence to twenty years.

On Monday, Berenson appeared in a Peruvian courtroom and pleaded for the judges to allow her and her son to leave for the United States in order to seek medical treatment. She apologized to the people of Peru.

LORI BERENSON: [translated] If my participation contributed to societal violence, I am very sorry for this. If my coming to Peru has meant more harm to the country, I am very sorry for this. And those who are affected by my words or actions, I ask their forgiveness.

AMY GOODMAN: Lori Berenson also told the court she does not pose a danger to anyone.

LORI BERENSON: [translated] I lament the repercussions that my parole has had on society. This has always been a media case, since I was detained. The truth is, despite how it hurts me, I accept that I have been ostracized, but according to the law and based on my behavior, I do not represent a danger for anyone.

AMY GOODMAN: For more on the story, we’re joined on the telephone by Lori Berenson’s mother Rhoda Berenson in Lima, Peru. Rhoda and her husband Mark run the website freelori.org.

Rhoda, welcome to Democracy Now! Can you explain what has happened? Why has your daughter Lori and her son Salvador, your grandson, been reimprisoned?

RHODA BERENSON: Hi, Amy.

There was an appeal on Lori’s parole. Right after she was granted parole in the end of May, the state prosecutor appealed that. That’s a process that’s permitted. Either side can appeal. And that was what was being studied in the courtroom, and there were papers that went back-and-forth on Monday. And there were a couple of main issues that the prosecutor had brought up, namely that Lori did not serve a full fifteen years—that’s three-quarters of her sentence—but had been shorter, because she had worked. If you do work-study time, you can shorten that. It’s a standard procedure, and that’s how everybody had done it in the past.

And there was also an issue about the apartment that I’m right now sitting in, as to whether or not the police had seen the apartment prior to the decision to giver her parole. The police come and check that the apartment really exists and that people aren’t saying they’re moving someplace that doesn’t really exist. So that was what the issue was, the decision yesterday, that because the apartment hadn’t been checked before the judge granted parole, that the apartment must be checked, the judge then has to say the apartment was checked and then, once again, decide whether or not to give Lori parole, and that, in the meantime, Lori must return to prison. So, because there was a technical error, because the judge did not order the house inspected, Lori had to return to prison until this is all settled.

And it’s absolutely outrageous. And actually, after—while Lori was living here, the police do come and check once a month. That’s a standard parole procedure that every—so they’ve been here. It was all ludicrous. I mean, there was a famous Peruvian lawyer who was last night saying it’s, you know, just ludicrous to send her back to prison until you finish that up, because then they can appeal again. So they haven’t really decided on any issues other than this technicality. So I know it’s probably complicated for your listeners, but there was a technicality in the original decision to giver her parole, and Lori had to be imprisoned until that is resolved, which will probably take a couple of months, at which point, we assume that that’s going to be taken care of. The judge will once again say she’s granted parole. She’ll then be out on parole again. But then again, this is Peru, so you never know. But that’s what our assumption is. But then it may be appealed again. So, this is—this is something that only happens to Lori Berenson. You know, we’ve been at this for fifteen years. Hundreds of Peruvians who have been involved in political terrorism cases have—[no audio]

AMY GOODMAN: Rhoda?

We seem to have lost Rhoda Berenson, mother of Lori Berenson. Again, she has been reimprisoned along with her son Salvador. Rhoda Berenson, speaking to us from Lima.

Rhoda, did we reestablish a connection?

RHODA BERENSON: Yes, I’m here. When did you lose me?

AMY GOODMAN: Just in the last second. Juan?

JUAN GONZALEZ: Rhoda, I’d like to ask you, you were mentioning the—this is Peru. As you were talking, we were showing some of the video to those of our audience that have video access or TV access, showing the frenzy of the press around this case. Could you talk about the climate in Peru ever since Lori was released?

RHODA BERENSON: Well, the climate has always been like that for Lori, if anything happens and her name is mentioned. But the press in Peru—[no audio]

AMY GOODMAN: Hmmm. Well, I’ll tell you what we will do. We will go to a break, see if we can get her back on. Rhoda Berenson is who we’ve been talking to, mother of Lori Berenson. Lori and her son have been reimprisoned to serve out the full twenty-year sentence, after she’s already served fifteen, though her mother says this may be a technicality and she could be out sooner. This is Democracy Now! We’ll be back in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We’re trying to have an uninterrupted conversation with Rhoda Berenson, the mother of Lori Berenson. Lori has just been reimprisoned in Peru. Juan?

JUAN GONZALEZ: Well, yes, before we were cut off, Rhoda, I was asking you about the media reaction to Lori’s release a couple of months ago.

RHODA BERENSON: Well, the reaction was horrendous. You know, there is nothing Lori can do that they don’t turn against her. And they’re physically—when, any time either Lori, I or—last night was Lori and her baby, were almost crushed. I mean, the baby was screaming, because the priests come swarming right in on you. And, of course, when that happens, the immediate media reaction was, "Well, she shouldn’t have had her baby with her." You know, this is like—you know, it’s like blame the victim kind of thing, when, of course, if she didn’t have her baby with her, they would have yelled, "She doesn’t have her baby! She’s abandoned her baby!" There’s nothing Lori can do that they don’t twist in a negative way. I mean, nobody knows her real story. Nobody knows that she was not convicted of being a member of a terrorist group, that she was acquitted of that. Nobody knows that. They make up any—she can walk down the street, and they call her assassin. You know, she’s certainly never assassinated anybody. Nobody knows the facts. They just quote anything they like. And it’s—so, for the entire time she was out, there were articles every single day about Lori Berenson, Lori Berenson, Lori Berenson.

AMY GOODMAN: Were you afraid for her—

RHODA BERENSON: Are you still there?

AMY GOODMAN: Yes. Were you afraid for Lori and her son Salvador’s safety during the period that they were out?

RHODA BERENSON: We had—there were some threats. You know, we were nervous. I really didn’t expect anyone was going to physically attack either of them. And, you know, I would say a huge majority of the population is anti-Lori, but we still managed to walk the streets and have people come up to us and say, "Lori, not everybody’s like that. We’re on your side." So, it was—yes, we’re always nervous here, because people recognize us.

AMY GOODMAN: Rhoda, can you explain what Lori was convicted of?

RHODA BERENSON: She was convicted of renting an apartment which was used by the MRTA. Also, at the time, she had been charged with being a member of the group and helping plan things or—you know, all of that, she was acquitted of. So she was found guilty of renting the apartment for her. And I think in her little speech the other day, she said she accepts responsibility for that.

AMY GOODMAN: Has Salvador, her son, gotten the operation that he needs?

RHODA BERENSON: No, that’s scheduled for November. And certainly we’re hoping that Lori is out on parole. And, you know, with the Peruvian public feeling so uncomfortable, for whatever reason they have, with her, it just makes sense, in my mind, that they all say, "Throw her out of the country."

AMY GOODMAN: Does she want to come to the United States?

Well, we lost Rhoda Berenson again, but we’ll have to leave that for another day. Rhoda Berenson, the mother of Lori Berenson. Again, Lori Berenson and her son Salvador, fifteen months old, have been put back in prison after serving fifteen years. Lori faces another five.

Republished from Democracy Now

JUAN GONZALEZ: We begin today’s show in Peru, where a three-judge panel has ordered the American activist Lori Berenson back to prison to serve the remaining five years of her twenty-year sentence. Berenson and her fifteen-month-old son Salvador had been free since May, when she was released on parole.

Berenson is the American activist who was arrested in 1995 in Lima, accused of collaborating with the rebel group Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement, or MRTA. She was initially sentenced to life in prison for treason, but four-and-a-half years later, due to international pressure, her sentence was vacated. She was retried by a civilian court, which reduced her sentence to twenty years.

On Monday, Berenson appeared in a Peruvian courtroom and pleaded for the judges to allow her and her son to leave for the United States in order to seek medical treatment. She apologized to the people of Peru.

LORI BERENSON: [translated] If my participation contributed to societal violence, I am very sorry for this. If my coming to Peru has meant more harm to the country, I am very sorry for this. And those who are affected by my words or actions, I ask their forgiveness.

AMY GOODMAN: Lori Berenson also told the court she does not pose a danger to anyone.

LORI BERENSON: [translated] I lament the repercussions that my parole has had on society. This has always been a media case, since I was detained. The truth is, despite how it hurts me, I accept that I have been ostracized, but according to the law and based on my behavior, I do not represent a danger for anyone.

AMY GOODMAN: For more on the story, we’re joined on the telephone by Lori Berenson’s mother Rhoda Berenson in Lima, Peru. Rhoda and her husband Mark run the website freelori.org.

Rhoda, welcome to Democracy Now! Can you explain what has happened? Why has your daughter Lori and her son Salvador, your grandson, been reimprisoned?

RHODA BERENSON: Hi, Amy.

There was an appeal on Lori’s parole. Right after she was granted parole in the end of May, the state prosecutor appealed that. That’s a process that’s permitted. Either side can appeal. And that was what was being studied in the courtroom, and there were papers that went back-and-forth on Monday. And there were a couple of main issues that the prosecutor had brought up, namely that Lori did not serve a full fifteen years—that’s three-quarters of her sentence—but had been shorter, because she had worked. If you do work-study time, you can shorten that. It’s a standard procedure, and that’s how everybody had done it in the past.